Go to Part I: [Online or Offline?] Part I: Residue of the Past

Mike Rugnetta says no and I agree. In part one of this post series, I wrote about how many users think about digital data and tools as digital replicates of tangible tools and content because they learned computing during a transitional period between tangible tools to digital tools. I concluded, however, that as the user base for these digital tools loses that connection to this legacy, the line between online and offline becomes ambiguous. In this post, I will dive into that complexity.

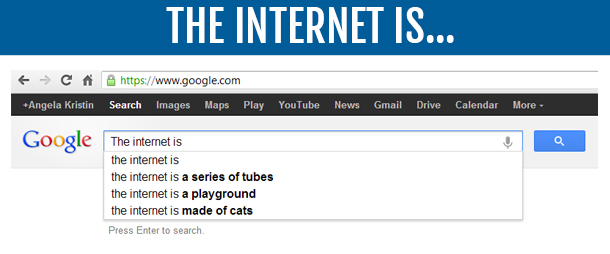

What is the Internet?

This seems like it should be simple.

The Internet is a global system of interconnected computer networks that use the standard Internet protocol suite (TCP/IP) to serve billions of users worldwide. (Wikipedia)

However, the technical definition, like the one above from Wikipedia, doesn’t describe the average understanding of the internet for most users.

When I was a kid and the Internet was in its infancy (I know, I am older than the Internet, it’s crazy), it was really clear when you were on the Internet and when you were not. When you were on the Internet, you were using a huge desktop computer, you had to connect to the Internet while listening to horrid screeching noises, your mom was upset that you were tying up the phone line, and to do anything on the Internet (e.g. finding a webpage or chatting) required more effort and knowledge than today. However, with smartphones, tablets, desktops, laptops, ultrabooks, netbooks, eReaders, Smart TVs, VoIP Phones, smart watches, connected cars, and Google Glass, there are many gateways to the Internet. Many of these devices are always connected or connect automatically. Now, moms are angry that kids are not paying attention to the “real world” because the ease of connecting means that there is less pressure to not be on the Internet. Then, with WYSIWYG editors, social media, super-massive search engines, and the like, interacting with the internet involves much less specialized skill, content is more accessible, and content production is growing rapidly every day. Through these tools, the Internet has become more integrated with our everyday lives.

The Internet has come to mean much more to it’s users than just a network that communicates over TCP/IP. The Internet isn’t restricted to one activity in one place. With the depth of the Internet’s penetration into our lives, can we say that being engaged with the Internet is being online? Is being engrossed in surfing the web on a laptop the same kind of online as receiving a notification of new email on your phone? Does the device you use or the tasks you perform impact your online-ness?

What is online?

Online is complicated. There are two general ways that I have commonly heard “online” used: as an action and as an altered state. These usages do not encompass my observations of user behavior and are rooted in outdated ideas of the Internet that no longer apply to the way most people experience the Internet. However the usage of online as identity is far more compelling. Yet, this usage drastically alters what it means to be online and brings its own host of complications.

Online as Action

Saying, “I’m going online…” or, “he went online…” implies agency, an intentional and knowledgeable action. This made sense in the early days of the Internet when one must take a static position in front of a machine and invest time in the action. To go online, was not something someone could do accidentally or do without knowing. However, today, “going online” could happen anywhere and doing so requires very little disruption to other behaviors.

Further, technology has made the things we do online much easier and less agentive by not passively waiting for a human to seek out the Internet. With notification systems in browsers, operating systems, and phones, “online” comes to us. If I sit reading a book and my phone dings as a new email hits my inbox, was I online? I was not intentionally engaging in online behavior. However, I was nevertheless interacting with the Internet. Even if I chose not to check the email, I was still aware of the Internet and learning information from it.

Online as an Altered State

This is the use of online that mom’s use to complain about their children losing touch with the real world because they spend all of their time online. It is not uncommon for “being online” to be discussed as if the individual were in an altered state, out of touch with one’s context because of the Internet’s overabundance of sensory stimuli. As if being online were akin to a dream-like state where one’s relationship to body, time and environment are displaced or modified.

While some online behaviors (e.g. MMORPGs) may have enough immersive power and abundance of stimulation that one could make an argument that such behavior causes an altered state, most online behaviors are not. Rather, I would argue that most online behavior is multitasked with multiple online behaviors and offline behaviors which break up the immersive experience. The online and offline experience bleeds together nearly seamlessly.

Additionally, although the Internet contains a wealth of information and media, the user is not experiencing the totality of the Internet when online. Rather the user can only view a very small portion of the Internet at any one time. Even on large social media services like Facebook and Twitter, the user only views a minuscule portion of the data stored within these services. Therefore the necessary increase in stimulation required to trigger an altered state is missing. The actual intake of information from online behaviors is not greatly increased from the intake of information offline despite the almost inconceivable amount of information available.

Online as Identity

This usage of online describes a person who has a representation of their identity on the Internet and have internalized this online identity as part of their self knowledge. As in “Are you online?” “Why yes; I’m on Facebook!” These online representations in the forms of profiles, avatars, and digital footprints, act as a constant presence that can be viewed and interacted with by others — even when the individual is “offline.”

With the proliferation of technologies and their encroachment into everyday behavior, this online representation becomes more important as offline representations are copied to and articulated with digital representations through photographs, tweets, SMS messages, and check-ins. In this way, being online becomes an integral part of self and drastically alters one’s behavior when one is both “online” and “offline.” From documenting offline behaviors and representations online (e.g. Instagram-ing one’s dinner) to augmenting offline behaviors with online activities (e.g. reading IMDB trivia on one’s phone while watching a movie).

Of the three usages outlined here, this is the one I find most compelling and the most accurate in describing my observations of the online/offline distinction. However, if this is what it means to be online, then when is someone not online? There are, of course, individuals that do not engage with the internet actively. However, how much interaction is needed before one is online? Is an individual who does not use the internet really truly offline? My great-grandmother only used the internet when she was being forced to by some young family member to do so. She did not have email or Facebook. Yet, she had an online presence in digital phonebooks, ancestry.com, several digital newspaper articles and she was lovingly represented in her funeral’s online guestbook. Additionally, there are many photographs of her and posts about her on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and now this blog. Was my Grandma online or offline? If others could engage with her online representations, was she still considered offline?

What about celebrities that refuse to use the internet, such as Christopher Walken who doesn’t own a mobile phone, a computer or an email address. Yet, Walken is all over the internet in biographies, movie clips, music videos, internet memes, and more internet memes.

Even if we limit the online identity to someone who actively participates in building digital representations of themselves, how does distinguishing this person as online become a valuable distinction? Wouldn’t the distinction be subject to all the same critiques as other identity categories, including those of American and European bias? As an anthropologist, how useful is this distinction? Is the distinction as Mike Rugnetta says just an arbitrary line in the sand?