Well, Internet, I am humbled by your affections. The post I wrote last Sunday about the Crying Chief Raoni meme has gotten 103,000 unique visitors from 197 countries in the last week. For a blog that usually ranges around 50-100 unique visitors a week, that is pretty amazing. Thank You!

All of those new readers brought in a lot of thoughts and ideas. So, I thought that I would write a follow-up post to talk about this issue with a bit more nuance.

There have been a few critiques from readers that argued that the problem was the falsehood in the meme and that my further assertions were dubious.

“This pulls into focus our own arrogance and biases against indigenous peoples. It does not help the cause or support Chief Raoni. It only makes us feel better about our lazy attempts to “save” people that we look down upon.”

There were two main arguments against this: (1) I shared it and that doesn’t describe me, and (2) the ends justify the means.

I shared it and that doesn’t describe me!

Should you Google claims you see in memes before re-posting them? OMG, yes!

However, does sharing the Crying Chief Raoni meme make you a bigot? No.

One of my favorite Anthropology 101 sayings is “Racism is not just for racists!” or, in this case, “Prejudice isn’t just for bigots.” Almost no one thinks that they have biases or prejudices; but, everyone does. From the time we are born, we are surrounded by cultural knowledge and as we navigate our lives, we use that knowledge to understand our surroundings. Most of our biases are seen as completely socially acceptable to the extent that we often do not even realize that we have them.

Practice theory, as presented by great social scientists like Pierre Bourdieu, Anthony Giddens and William H. Sewell, argue that human’s don’t just interact with the world directly. Our culture places layers of meanings over the objective world that we use to understand the world and our relationship to it. These layers of meanings are our habitus and that habitus plays a powerful role in every choice that we make, including how we represent ourselves and others.

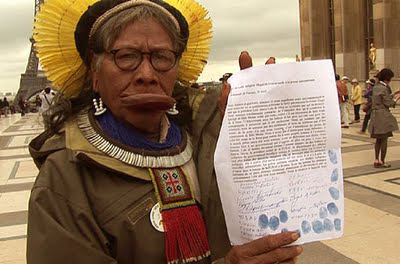

I choose to believe that nearly every person who shared the Crying Chief Raoni meme was genuinely moved by the story and posted the image out of empathy (except, perhaps, the original writer who lied). However, the issue I have with this meme isn’t the individual motivations of sharers. It is the habitus that these people share and how the proliferation of the meanings associated with the Crying Chief Raoni meme bolster the part of our habitus that represent indigenous people as powerless and in need of non-indigenous benevolence to survive. The habitus that allows us to see a picture of a crying man and use it to justify silencing his voice.

Individual’s motivations and intentions do not directly correlate to actual consequences in larger social discourse. When taken en masse, the collective discourse paints a different picture than was intended. Rather than depict the struggle of Chief Raoni in a way that accurately represents Chief Raoni and his people, it frames the discussion around narratives that are important to the reader. It plays on the fears of many Americans (and others too) that we are becoming ignorant of the world in favor of wasting our intellect on, “the lives and love affairs of movie actors and actresses, football players and other celebrities.” It addresses the reader’s concerns that our “quality of life” and “modern comforts” are having an impact on the environment and are leading to an oppressive globalization of so-called-western ways of life. These are valid issues; however, they are not the narrative that best describes the Belo Monte Dam and the Kayapó people.

The narratives that are presented from Chief Raoni and related activists are not about globalization or anyone else’s “modern comforts.” The narratives are about the rights of indigenous people as part of the state of Brasil.

The energy policy of the Brazilian president, Dilma Rousseff, is not only in contradiction to the constitutional principles of the country, but it is also in complete violation of the international commitments taken by Brazil itself. [Source]

I am against this because indigenous people are part of the State of Brazil and as such must be duly consulted and must take part in the country’s developments, which is also ours. I am against this because the State endangers indigenous peoples’ lives and cultures while causing unprecedented environmental destruction. [Source]

By sharing and endorsing the Crying Chief Raoni Meme, you do not become a bigot. It does not change your identity. However, it does change the representation of Chief Raoni, his people, and his movement. It takes away his name and his voice and displaces him from his reality and repositions him as part of a narrative about us – our worries, our troubles. We make the nameless, crying indigenous man part of our habitus. This is why I say that, “This pulls into focus our own arrogance and biases against indigenous peoples. It does not help the cause or support Chief Raoni.”

The ends justify the means.

I dont understand your point. The main thing is that a dam is going to be built that will devastate the lives of many tribes. So what does it matter whether a picture is real or not? That is minuscule related to the suffering of the tribes, certainly is a lot less relevant. [Commentor Jason]

Jason was not alone in this argument and he is not wrong in the short term – i.e. there is no such thing as bad press. Awareness is an important part of activism. So, without taking into consideration anything other than the need for awareness, this is a logical argument.

However, there are two big issues with this logic: (1) the meme rather failed at getting people aware of how to help and (2) the meme does not exist in a vacuum where it has no influence outside of its intended consquences.

Meme Fail

I say that the meme rather failed because the easiest, free way to support the cause is to sign the online petition on Chief Raoni’s website. However, despite the popularity of the meme over the last two years, only 440,285 people have signed it since 2010. That number is impressive for the actions of only a small group of dedicated people. However, successful memes that call people to action can pull in support that makes 440,285 signatures in three years look miniscule. Consider that it only took two weeks for the petition for the prosecution of Trayvon Martin’s Killer to reach 500,000 signatures. It only took 24-hours for The Oatmeal to raise $100,000 dollars to protest his legal issues with FunnyJunk.

Not in a Vacuum

When you save someone, you imply that you are saving her from something, you are also saving her to something, What violences are entailed in this transformation, and what presumptions are being made about the superiority of that to which you are saving her? Projects of saving other women depend on and reinforce a sense of superiority by Westerners, a form of arrogance that deserves to be challenged.

(Abu-Lughod 2002:788-789)

Abu-Lughod was talking about the narratives of saving Muslim women Post-9/11; however, her overall argument about salvation narratives in general applies to the Crying Chief Raoni meme as well. While the people who shared the meme intended to do “good,” by sharing the meme they were actually sharing a problematic narrative of saving. Once a discourse is built around saving, the people who need to be saved become simplistic charactures that fulfill roles in the narrative rather than their rightful place as authors of their own narrative.

By removing Chief Raoni’s name and removing his words from the discussion, he loses his place as the agent of change. The agent of change becomes the reader. The reader is empowered with creating the narrative of change: how it occurs and on what terms. This adjustment means that the actual needs and desires of the people impacted by the action are not represented. While the reader wants to stop the dam and preserve the way of life of the Kayapó, Chief Raoni is arguing for a voice in the development of his country. He also wants to stop the dam; however, this is a short term solution to a larger problem. If the dam is stopped by some benevolent third party that is divorced from Chief Raoni’s efforts, then this third party has only solidified the silencing of indigenous people.

So, no, the ends – either intended or actual – do not justify the means.

Want to Actually Help?

A few people asked what they should be sharing to support Chief Raoni. Use the words that have been chosen by the affected individuals and use images that empower them. Then use a call to action that directs people to Chief Raoni.